Person with 2 plastic crates of valerian salad, Unsplash.

When you bite into a tomato grown on your balcony or from a nearby farmer’s market, you’re participating in something bigger than a meal. You’re part of a food system, the interconnected network that links soil, seeds, farmers, distributors, and consumers.

But as global disruptions to supply chains — from the Covid 19 pandemic to extreme weather, to geopolitical tensions, and supply chain disruptions — become more common, one question emerges: how resilient are our systems and links to food?

Understanding Food Security

Food systems resilience is the capacity of food networks to withstand and recover from disruptions, while continuing to provide nutritious, affordable, and sustainable household food security for all.

A resilient food system is one that adapts, absorbs shocks, and evolves. Resilience stems from diversity, equity, and ecological health, qualities that modern industrial agriculture has often sidelined in pursuit of efficiency.

Before we can build resilience capacity, we need to understand what food security entails. FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) identifies it as existing “when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.” This definition dates back to The State of Food Insecurity 2001 and encompasses 4 critical dimensions:

- Availability. Is there enough food produced and supplied? This accounts for agricultural production, food stocks, and trade.

- Access. Can people obtain food through purchase, production, or assistance? Economic access is particularly crucial here, as having food available in markets means little if people cannot afford it.

- Utilisation. Are people able to use food properly through adequate diet, clean water, sanitation, and healthcare? Nutrient-dense food loses its value if it cannot be safely prepared or properly absorbed by the body.

- Stability. Can people access adequate food at all times? Food security requires consistent access, not just occasional availability.

Food security and food systems resilience are deeply intertwined. When one pillar weakens, due to drought, inflation, or conflict, the entire structure becomes unstable. It's not enough to simply produce more food.

The Vulnerability of Our Current Food System

A convergence of multiple crises has exposed the fragility of our globalised food supply chains in the recent years. Let's now get into a detailed review of some important concepts in the context of the agricultural supply chain vulnerabilities of 2024-2025.

Climate Change

Climate disruptions are reshaping food production in real time. Droughts, floods, and extreme temperatures have broken traditional agricultural cycles worldwide.

May 2025 joint modelling Building Resilience in Agrifood Supply Chains by Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and Quantis, projects potential falls in global production of up to 35% by 2050. They foresee an average decline of 12% across 15 major crops (both staples and non-staples), which account for ~65% of global crop production and ~70% of global caloric intake. These statistics represent real threats to our ability to feed growing populations.

Geopolitical Tensions and Trade Disruptions

The Russia-Ukraine conflict demonstrated how quickly geopolitical events can destabilise global food systems. Export and import bans on some of the world's largest food commodities led to price inflation and increased vulnerabilities for geographies heavily dependent on international markets.

These events reveal that highly centralised food distribution networks lack the flexibility to respond to disruptions.

The Covid-19 Pandemic

As logistics were disrupted and labour shortages emerged in the context of Covid-19, we witnessed how quickly the system could falter. The ripple effects touched every link in the chain, from farm production to retail distribution. For many communities, particularly those already facing food insecurity, Covid-19 and other shocks had devastating consequences.

The Nutritional Decline of Fruits and Vegetables

Even when food is available, its nutritional quality isn’t guaranteed. Studies comparing modern crops to those from decades ago reveal that many fruits and vegetables now contain fewer vitamins, minerals, and proteins than they once did.

Why is this happening?

- Intensive farming practices. High-yield varieties often prioritise growth rate, size, and shelf life over nutritional quality.

- Soil health decline. Decades of monocropping and chemical inputs have depleted organic matter and microbial life, reducing nutrient transfer to plants.

- Ecosystem degradation. Deforestation, loss of pollinators, and erosion further weaken natural nutrient cycles.

What Soil Health Means for Resilience

Without crop rotation or diverse plantings, soil run out of microbiomes over time. Plants grown in such compacted, depleted soils simply cannot access the necessary minerals and compounds that make them nutritious, no matter how much synthetic fertilizer is applied.

The continued extraction of soil resources without replenishment accelerates environmental system decline. This decline is produced to the detriment of public health. Reversing this trend has to do with soil health restoration in favour of resilient agriculture and food systems. Healthy soils also retain water better during droughts, resist erosion during floods, and support nutrient-dense crop production.

A food system that provides sufficient calories but inadequate nutrients cannot truly be called secure. Malnutrition (including both undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies) weakens populations' ability to withstand health crises, and perpetuates poverty.

The Building Blocks of Food System Resilience

Enhanced food system resilience that can withstand shocks requires fundamental reorientation. Several approaches show promise, though they come with both opportunities and challenges.

Plant sprouting in a field, Unsplash.

Regenerative Agriculture: Promise and Pitfalls

Regenerative agriculture aims to restore soil and ecosystem health through practices like cover cropping, composting, reduced tillage, and agroforestry. The FAO supports regenerative approaches for enhancing soil fertility, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration.

Transitioning to regenerative practices can temporarily reduce yields or require new equipment and training, with costs often falling on smallholder farmers rather than the corporation. Without fair compensation, such initiatives risk reproducing the same power imbalances they aim to fix.

True regeneration is all about the ability of food system actors to adapt their activities to resist disruptions and share responsibility.

The Corporate Cooptation Problem

Companies such as Nestlé have pledged to embrace these methods at scale. The company’s goal is for 50% of its ingredients to come from regenerative farms by 2030, supported by a network of agronomists working with producers globally.

While Nestlé’s investment in soil health and agroforestry is welcome, questions remain about accountability, equity, and farmer burden. A 2022 estimate by the Changing Markets Foundation and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy reveals that Nestlé's climate roadmap failed to align with the 9 recommendations from the UN Integrity Matters: Net Zero Commitments by Businesses, Financial Institutions, Cities and Regions report. The company has been accused of overreliance on regenerative agriculture as a solution while its methane emissions have barely dropped, even while Nestlé claims progress. To say the least, the Swiss multinational left Dairy Methane Action Alliance in early October 2025.

Industry watchdogs warn that the lack of agreed scientific definitions and transparency around implementation creates opportunities for companies to apply “regenerative” labels to practices that barely scratch the surface of systemic change. Research by the sustainability investor network FAIRR found that while 63% of studied agri-food companies referenced regenerative agriculture's potential, 64% of those companies had not established any formal quantitative targets to achieve their stated ambitions.

This corporate appropriation matters because it risks reducing genuine regenerative agriculture to a marketing buzzword. This trend ends up undermining farmers who are doing the real work of reorientation.

Agroecology: A Holistic Alternative

Agroecology combines ecological resilience concepts with social justice. In doing so, it places stronger emphasis on the social and the political context of food: on who controls land, labour, and decision-making.

It views farming as part of a living system, connected to water, climate, culture, and community. This entails:

- Polycultures and crop rotation that mimic natural ecosystems, building soil health while reducing pest pressure.

- Natural pest management through biodiversity and beneficial insects, eliminating reliance on chemical pesticides.

- Agroforestry that combines trees and shrubs with crops, creating microclimates, preventing erosion, and enhancing carbon sequestration.

- Water management that works with natural hydrology rather than against it.

- Knowledge sharing that values farmer expertise and traditional ecological knowledge alongside scientific research.

Agroecological practices such as intercropping, composting, and maintaining local seed diversity restore biodiversity and significantly strengthen food sovereignty. Thus, they ensure communities have agency over what they grow and how they do it.

Barcelona Healthy and Sustainable Food Strategy 2030 exemplifies agroecology in action. The city plans to offer informal training in agroecological practices supported by intergenerational knowledge transmission. They're extending the Collserola Agricultural Contract and introducing AMB subsidies for the Muntanyes del Baix and the Serralada de Marina projects. Such subsidies will be conditional on productivity, biodiversity conservation, water retention, and carbon storage. This ensures that support goes to farming that genuinely builds up resilience.

The Power of Local Food Systems

Perhaps the most critical strategy for building resilience is strengthening local food systems and links. When communities can produce a significant portion of their food locally, they become less vulnerable to global supply chain disruptions.

Community-supported agriculture (CSA) and farmers' markets create direct connections between producers and consumers, keeping more value within local economies while reducing transportation emissions. Barcelona City Council lets us know that self-sufficiency in fruits and vegetables currently is at 15% in the Province of Barcelona.

Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture

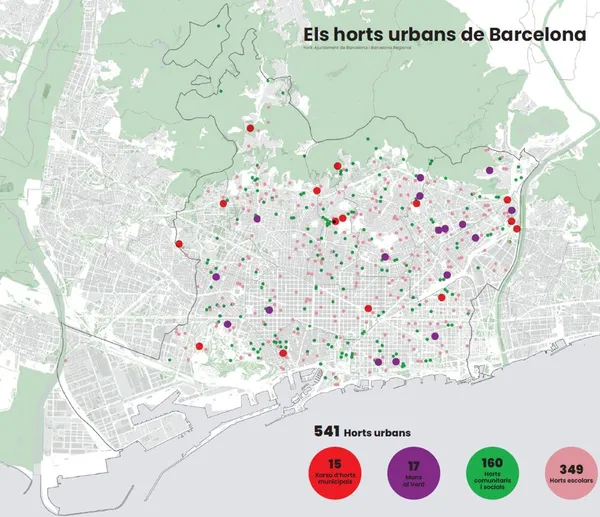

Cities have remarkable potential to contribute to food production. Barcelona's Urban Agriculture Observatory maps 541 urban allotments, accounting for 160 community gardens, 349 school allotments, 15 municipal gardens, and 17 linked to the “Mans al verd” programme. Barcelona Metropolitan Area aims to increase its agricultural land from 9.3% to 13-15% by 2030.

Barcelona’s urban allotments, 2019-2030 Urban Agricultural Strategy, Urban Agriculture Observatory.

Green spaces mitigate urban heat islands, help manage stormwater, and support biodiversity. School gardens educate children about where food comes from while providing hands-on classes in ecology. Community gardens build social cohesion while producing fresh vegetables.

Peri-urban areas are equally crucial. Between 1956 and 2018, the Barcelona Metropolitan Area lost 80.5% of its agricultural land. Barcelona is working to restore disused agricultural land in areas like Parc Agrari del Baix Llobregat and Parc Natural Collserola.

Preserving Agricultural Biodiversity

Local food systems can preserve crop diversity that industrial agriculture has abandoned. Barcelona's strategy also proposes creating seed banks in community gardens to conserve local crops and wild edible species.

These traditional varieties often possess characteristics, such as drought tolerance or disease resistance, that make them invaluable for adapting to climate change. By maintaining these diverse seed stocks, communities ensure that seeds are passed down through generations.

Addressing the Challenges

Building food systems resilience doesn't come without obstacles. Let's carefully discuss its challenges.

Economic Viability

Farmers transitioning to regenerative or agroecological practices often face initial yield reductions before systems stabilise. Financial support is essential during this transition period. Barcelona offers land leasing assistance, housing subsidies, and grants for infrastructure modernisation. In this way, it ensures fair access to the land to the unemployed, young people and women undertaking agroecological projects.

Scale and Capacity

Local food systems alone cannot feed dense urban populations entirely. Realistic resilience strategies must integrate local production with regional and international supply chains. The goal is diversification among food systems, making sure that communities have multiple sources of food.

Equity and Access

Food systems resilience must address inequality directly. Higher-income consumers can more easily access farmers' markets and organic produce. Barcelona's strategy explicitly ensures that resilience-building doesn't inadvertently deepen existing disparities.

Training programmes and land access initiatives targeting vulnerable populations can in fact create economic opportunities while building resilience. When food insecurity disproportionately affects certain groups, solutions must specifically address their needs.

Climate Adaptation

Even as we build resilience, we must acknowledge that climate change will continue reshaping agricultural possibilities. Crops that thrived in certain regions may no longer be viable. Local food systems must be adaptive, experimenting with new varieties and species while preserving biodiversity that may prove crucial as conditions change.

Climate change equally threatens the productivity and the profitability of the agricultural sector. Farmland value in parts of southern Europe is expected to decrease by more than 80% by 2100.

Urban allotments, Unsplash.

The Food System Is at a Crossroad

When it comes to food giants' commitments to building food resilence, the term "regenerative" doesn't mean much without clear metrics. Their lack of transparency directly undermines their credibility.

Policies can cause small producers disproportionate distress, when they lack the resources to meet new compliance standards without external support.

Meanwhile, consumer awareness is rising. More people care about the story behind their food: who grew it, how it was grown, and its environmental impact. Sustainable options still cost more.

Pilot projects are generating valuable insights. But scaling them up requires stable financing, technical support, and safety nets for farmers dealing with transition risks.

The challenge now is to bridge these implementation gaps without losing sight of what resilience truly means, namely the capacity to nourish people and planet under stress.

The Path Forward

Food systems resilience requires us to think about food as a fundamental human need that must be met through diverse, robust systems rooted in healthy ecosystems and strong communities. What can we do about it?

As individuals:

- Start or join community gardens to gain hands-on experience with food production.

- Choose produces grown using agroecological or genuinely regenerative practices when possible.

- Reduce food waste through better planning, preservation, and composting.

- Advocate for policies that support the resilience of local food systems and sustainable agriculture.

As communities:

- Create programs connecting vulnerable populations with training and resources for food production

- Establish seed bans and knowledge-sharing networks.

- Build relationships between urban consumers and regional farmers.

As policymakers:

- Provide financial support for farmers transitioning to regenerative and agroecological practices.

- Protect agricultural land from development, particularly peri-urban farmland.

- Establish procurement policies that prioritise local, sustainable food for public institutions.

- Invest in infrastructure for local food processing and distribution.

- Support research into climate-adapted crops and resilient farming systems.

Final Considerations on Food System Resilience

From Barcelona's comprehensive food strategy to countless local initiatives reconnecting people with the sources of their nourishment, reorientation is underway. Around the world, communities are already demonstrating that food systems can be simultaneously productive, sustainable, resilient, and equitable.

The question is whether we can scale and accelerate these changes quickly enough to meet the converging crises of climate change, geopolitical instability, and ecosystem degradation. The answer depends on our ability to make the right set of choices now. These decisions revolve around how we grow food, how we structure our economies, and what we prioritise as societies.

Truly resilient food systems operate in a way that makes access to nutritious food as a basic right for everyone. It means recognising that our wellbeing is inseparable from the wellbeing of the land that feeds us.

The path forward requires us to be simultaneously pragmatic and visionary, as we work with what we already have at hand while we prepare for the longer-term future. Most importantly, we need to remember that resilience emerges from the collective efforts of a set of different stakeholders (farmers, consumers, communities, and policymakers) working together towards a common goal.

By embracing regenerative and agroecological principles, we can grow a food system that is truly rooted in care, justice, and renewal.